Preventing Food Fraud: What You Need To Know

By Clare Winkel

Different countries have different food fraud regulations and often they even define the words according to their own unique priorities. If you are exporting, you need to know what the legal requirements are, as well as what the term itself means in different regions of the world. However you define it, though, food fraud in general is about economically motivated adulteration of food. It’s all about money, not sabotage.

For example, food fraud is not related to work in the area of Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP). HACCP is about the prevention of unintentional or accidental food safety adulteration. It is science-based and centres around food borne illness. Food fraud is different and separate from Food Defence, which is about the prevention of intentional ideologically-motivated adulteration such as would happen in a case of sabotage or bioterrorism.

Here’s how some countries have defined food fraud:

Australia:

• Gaining a financial advantage or causing a financial disadvantage through deception or dishonesty

Canada:

• the deliberate and intentional substitution, addition, tampering or misrepresentation of food, food ingredients or food packaging for economic gain

UK:

• the deliberate and intentional substitution, addition, tampering or misrepresentation of food, food ingredients, or food packaging, or false or misleading statements made about a product for economic gain.

USA:

• Intentional adulteration from acts intended to cause wide-scale harm to public health, including acts of terrorism targeting the food supply

• Hazard may be intentionally introduced for purposes of economic gain

Each country has its own set of regulations in place to protect consumers from what their government has defined as food fraud, but in addition to meeting the regulations in your country of manufacture and sale, and in the country to which you are exporting, you need to be aware of the requirements of the standards your company is audited against—i.e. BRC or SQF—plus any additional requirements your customers might have. For example, some retailers specifically require a ranking of identified food fraud hazards.

All GFSI standards have some type of documented Food Fraud Risk Assessment and Control Plan requirements, but even those vary. Some requirements are:

BRC Food Safety Global Standard:

• 3. 5.1.1. Documented risk assessment of each raw material that must consider substitution or fraud.

• 4.2. Documented assessment of the vulnerability of the raw material supply chain.

SQF Systems Elements Edition 8-Manufacturing:

• 4.4.5. A food fraud vulnerability assessment including the site’s susceptibility to raw material or ingredient substitution, mislabelling, dilution & counterfeiting… impacting food safety.

• 7.2.1 A food fraud vulnerability assessment that includes the site’s susceptibility to product substitution, mislabelling, dilution, counterfeiting or stolen goods which effect food safety.

One way to measure the risk of food fraud in raw materials is to embrace Vulnerability Assessment Critical Control Point (VACCP) in your operation. There are several methods that can be used, but some require far more resources in terms of staff knowledge, time and capability than is available in the average food business.

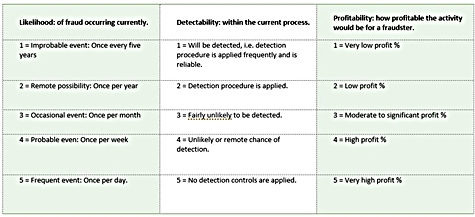

The most effective VACCP systems rank the potential food fraud risk of raw materials. Ideally you want to use the existing skills of your HACCP team and utilise a 3-variable matrix (Likelihood x Detectability x Profitability) and assess each specific raw material at least once a year.

What does a VACCP Risk Assessment actually look like?

What variables should be considered for review?

Food fraud can be a complex area that is rife with risk and, at times, uncertainty. Becoming well-informed about the possibilities for success in the area, and having the best team in place to support you, provides the most promising path to success.

About the Author

Clare Winkel is Executive Manager – Technical Solutions at Integrity Compliance Solutions and has audited or trained against GFSI standards in 13 countries. From 2006-2008 she helped design a process for the European Union to assess the farmed salmon supply chain for vulnerabilities and she later developed a method of ranking raw materials at risk of food fraud. In recent years she has spoken on food fraud at a number of international conferences.

Categories: A Global View, Food Contamination, Food Fraud

Tags: food fraud , food fraud assessment , food fraud hazards , food fraud vulnerability assessment , Food Safety